Introduction

In the first instalment, I looked at specific actions that the City and Park Board were engaged in relating to blueways and greenways.1 In this part, I will offer an assessment of these activities. The people I interviewed are employees of either the Engineering Department or the semi-autonomous Vancouver Park Board. They were the primary source of the information enumerated in Part 1, further elaborated on here.

A Multi-dimensional Assessment of the City’s Programs

Vancouver’s city programs represent a sustainable approach to urban environmental planning. First, they take a long-term perspective that seeks to partially undo more than a century and half of deforestation, land clearing, burying of streams, destruction of habitat, and paving of the urban landscape. Related to this, they take a ‘more-than-human’ perspective, considering the needs of other species of plants, animals, birds, and insects and their habitat requirements and beneficial interactions. They not only consider the needs of other life-forms but also pay attention to abiotic conditions such as water and soil, previously disregarded.

Secondly, these initiatives are conducted in ways that are holistic. For example, the Richards Street blue-green system increases the city’s tree cover, adds permeability, filters stormwater, and creates protected space for cyclists and ‘rollers’ of all kinds. In the case of the St. George Rainway, it pedestrianizes most of a four-block long space, and creates community gathering spaces featuring indigenous plantings, community art and interpretative signs. This interconnected series of gardens – celebrating a portion of the old course of St. George Creek – also increases permeability for rainwater and reduces the risk of flooding, having already proven its worth in a recent ‘atmospheric river’ event.2

In addition, these initiatives are occurring in the context of a robust, overlapping set of policies, such as the Rain City Strategy (and overlapping Healthy Waters Initiative), the Biodiversity Strategy, which in turn is linked to the City’s Bird Strategy, and an emerging Ecological Network plan.3 These policies and strategies involve a variety of actors – City and Park Board staff, residents, non-profits and businesses, as well as adjacent municipalities and Metro Vancouver. The City’s work employs different tools such as “regulation, advocacy, partnerships, and investments.”4

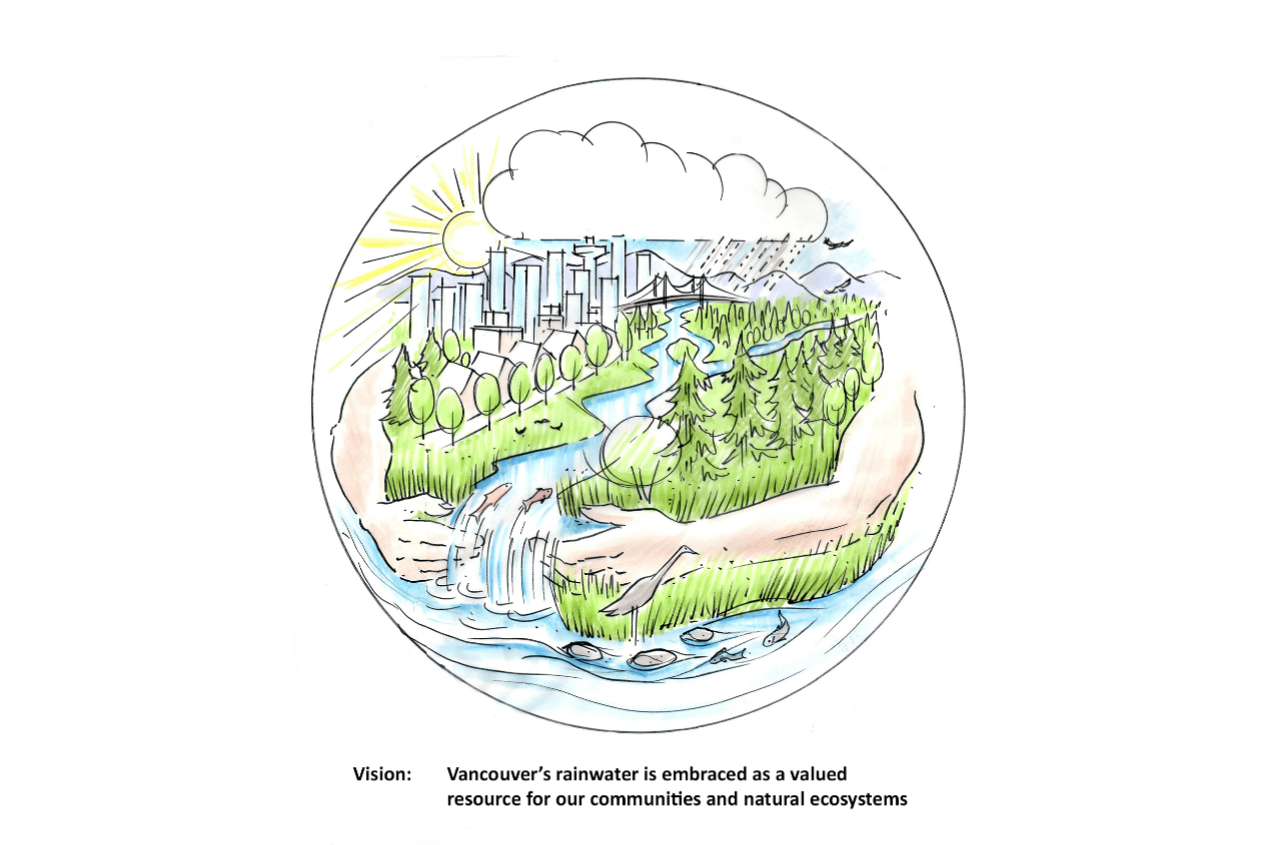

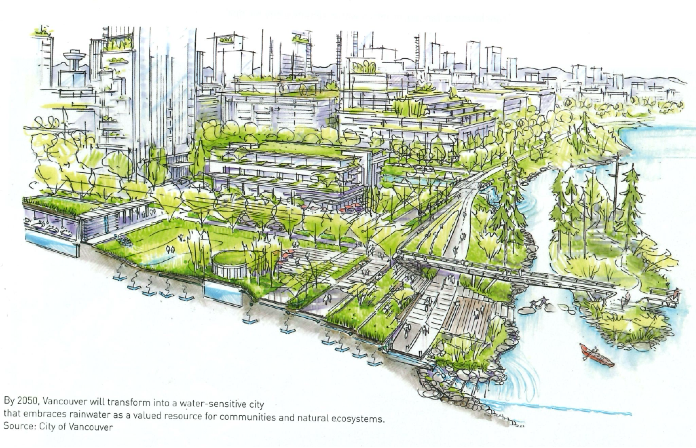

One example is the Rain City Strategy, first formulated in 2019 and which reflects a shift in paradigm and procedure with respect to how water is viewed and treated. The over-arching goal is to create a “water-sensitive city” with “different values, behaviours, and design principles.” The Strategy involves “using more natural ‘green infrastructure’ (GI) – natural systems, as well as engineered systems that mimic natural processes.” Instead of relying exclusively on underground stormwater pipes, the Strategy aims to introduce more “rain gardens, bioswales, green roofs, permeable pavement, engineered wetlands, and absorbent landscapes,” all of these being examples of green infrastructure.5

Figure 1: The ‘Water-Sensitive City’ [courtesy of the City of Vancouver]

Figure 1: The ‘Water-Sensitive City’ [courtesy of the City of Vancouver]

A positive feature of the Strategy is an emphasis on iterative planning/ adaptive management. Instead of going full-bore in a potentially wrong direction, it involves ‘learning by doing,’ and correcting mistakes as one goes along.6 There is also a strong focus on risk reduction and enhancing resilience, as described by McManus and de Hoog in relation to the Rain City Strategy:

For Vancouver, a changing climate means more intense rainstorms, overwhelming aging combined sewer and drainage systems, sending raw effluent into surrounding water bodies. Meeting sewer and drainage needs requires forward thinking, innovation, and collaboration to mobilize action. Vancouver’s Rain City Strategy is a long-term roadmap for holistic rainwater management – integrating green infrastructure solutions into land-use decisions, infrastructure upgrades, community plans, and urban design.

Equity is also considered. As these authors note…

The City is… looking at how GI co-benefits can be used to support and reinforce equity. Vulnerable populations including the elderly, infants, people of lower socio-economic status, and those experiencing homelessness are disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards and service deficits.

These service deficits also include less access to parkland and green space in poorer neighbourhoods than in more affluent ones. The Park Board’s VanPlay policy seeks to optimize recreation opportunities for all segments of the population.7

A final strength of the City’s approach is a strong emphasis on citizen participation and public awareness-building. The St. George Rainway began from a Master’s project in Landscape Architecture at the University of British Columbia by a student who lived in the neighbourhood. The idea was picked up by his neighbours, was incorporated into the Mount Pleasant Neighbourhood Plan, and eventually became reality.8

Figure 2: Activities accompanying citizen participation in the Beaconsfield Park wetland project. Photo by Carmen Rosen, courtesy of Still Moon Arts Society

Figure 2: Activities accompanying citizen participation in the Beaconsfield Park wetland project. Photo by Carmen Rosen, courtesy of Still Moon Arts Society

In Beaconsfield Park, a wet area prone to flooding was transformed into a wetland to provide habitat and serve as a stormwater reservoir. An initiative called Artists in Residence in Schools (AIRS) worked with elementary students to create artistic representations of the nature that had previously existed in the area and in nearby Gibby’s Field. A Squamish First Nations botanist taught the kids about plants, cameras were brought to enable them to peer into the stormwater pipes underground, and Still Moon Arts organized a ceremonial launch when the wetland was finally ready.9 These are just two examples of the City and its partners involving the community in environmentally beneficial actions.

Figure 3: More activities accompanying citizen participation in the Beaconsfield Park wetland project. Photo on the right by Yoko Tomita, courtesy of Still Moon Arts Society.

Figure 3: More activities accompanying citizen participation in the Beaconsfield Park wetland project. Photo on the right by Yoko Tomita, courtesy of Still Moon Arts Society.

Conclusion

Vancouver’s approach to deployment of green infrastructure, management of blueways and greenways, and enhancement of habitat and biodiversity, show strong evidence of future-oriented thinking, holistic approaches where each intervention fulfills a variety of goals, and strong overlapping policy frameworks. The work also emphasizes collaboration between City departments, the Park Board, residents, the private sector, and Metro Vancouver.

A potential vulnerability lies in lack of adequate funding for maintaining existing programs that were often launched with considerable capital investment, but without an accompanying commitment of resources for their maintenance. Another is the issue of changing political winds at City Hall. While current Council and Park Board leadership is more conservative than in past years, they appear to be willing to maintain existing programs. However, at present there is some doubt as to whether an independent Park Board will continue to be allowed to exist.10 Moreover, Council’s recent endorsement of a supposed ‘0% increase in property tax’ budget spells potential trouble for the staff and programs described above.11

The author is indebted to discussions he had with Vancouver staff – Jo Fitzgibbons, Julie McManus, Shannon Mendes, Marie Pudlas, and Jack Tupper.

-

‘Blueways’ refers to the work of rehabilitating, creating, and connecting watercourses. ‘Greenways’ refers to the work of enhancing and connecting natural and naturalized terrestrial spaces in an urban context. ↩

-

Rainway vs. atmospheric river. The Tyee, 2024. ↩

-

Rain City Strategy; Healthy Waters Plan; Biodiversity; Vancouver Bird Strategy; Ecological Network. ↩

-

“Transforming Vancouver into a Water-Sensitive City by 2050” by Julie McManus and Wendy de Hoog, Plan Canada, Summer 2020, pp. 28–31 [available from author]. ↩

-

Rain City Strategy. City of Vancouver. ↩

-

Rain City Strategy. City of Vancouver. ↩

-

Rainways could restore Raincouver. The Tyee, 2023. ↩

-

Presentation by Jo Fitzgibbons, Vancouver Park Board planner at “Next Chapter” annual conference of the Planning Institute of B.C., Vancouver, June 11, 2025; Still Moon Arts – Wetlands. ↩

-

Fumano, D. “Abolition of Vancouver park board will need to go to referendum.” Vancouver Sun, 9 November 2025. ↩

-

Vancouver passes budget that promises no tax increases, cuts millions. The Globe and Mail. ↩