There’s a well-known saying: “The purpose of a system is what it does.” No matter what a rule or policy is meant to achieve, what ultimately matters is the result it produces. This idea should be central to how our community thinks about its role in building a prosperous future for Nanaimo. Each resident—myself included—holds a personal vision of this city: a place of natural beauty and unique character, truly worth caring for. But we often hold conflicting beliefs, promoting noble goals while turning to quick fixes. These contradictions are making it harder to solve problems in a consistent or lasting way. That’s why the principle above is so important—it reminds us that success isn’t about what we meant to do, but what actually happens because of the choices we make together.

Nowhere is this dilemma more evident than in the discourse around housing. If I state, “housing is essential to the future of our community,” few would disagree. However, declaring that “development is essential to our community’s future” may raise eyebrows. While “housing” evokes positive associations, “development” often carries negative connotations—yet one is impossible without the other. Every home, after all, is the result of development. Many in our community assert that housing is a human right—but would they extend that same sentiment to “development”? I suspect not, myself included, as it doesn’t evoke the same powerful resonance. If housing truly is a right, yet community efforts frequently aim to restrict or halt physical change in their communities, aren’t we inadvertently denying many residents their fundamental right to housing?

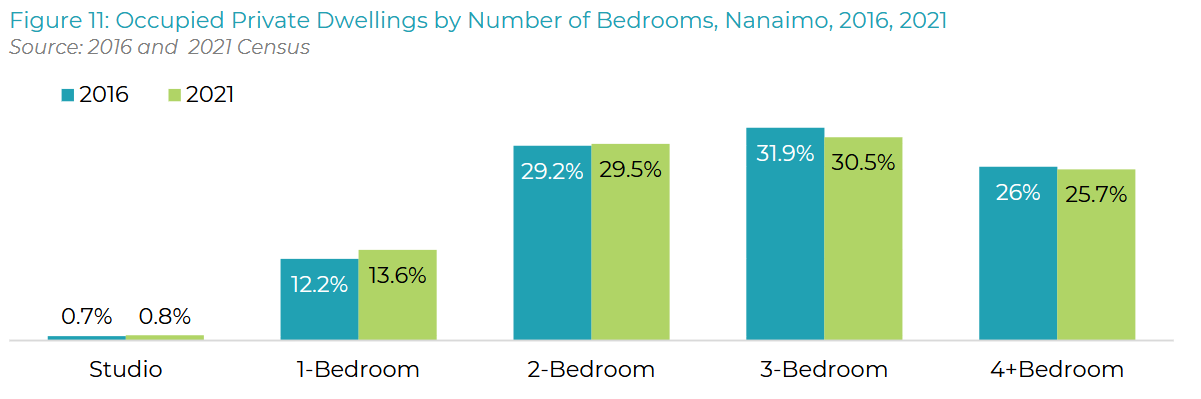

Since 2016, Nanaimo has seen a stable share of studio, 2-bedroom, and 4+ bedroom units, with a slight rise in 1-bedroom units and a decline in 3-bedroom units; over half of new units added from 2016–2021 were 1- and 2-bedrooms, driven by apartment development, though residents still report a need for larger family-sized housing. (Nanaimo Housing Needs Report)

Since 2016, Nanaimo has seen a stable share of studio, 2-bedroom, and 4+ bedroom units, with a slight rise in 1-bedroom units and a decline in 3-bedroom units; over half of new units added from 2016–2021 were 1- and 2-bedrooms, driven by apartment development, though residents still report a need for larger family-sized housing. (Nanaimo Housing Needs Report)

Our community will inevitably change—with or without new housing. Communities that resist physical change often pay for it by sacrificing the futures of their younger generations. Between 2006 and 2021, Oak Bay’s population grew by just 0.005%. In that same period, West Vancouver’s grew by only 0.045%. Both places have failed to build the housing necessary to allow new residents to live in their communities. In Vancouver’s Point Grey, similar resistance to change has contributed to soaring housing prices, making it nearly impossible for young families to live in the communities where they were raised. Consequently, school enrollments have declined, and closures now loom. This is just one of many pernicious outcomes. In the pursuit of preservation, we’ve excluded those born into our communities. Is a neighbourhood truly unchanged if its young families, nurses, and firefighters have been priced out? If we accept that “the purpose of a system is what it does,” then it appears that such a system prioritizes preserving the idealized homes of decades past over ensuring the prosperity of future generations.

“Homeownership is likely out of reach for single-income households like lone-parent and non-census families; these household types would need to spend close to 50% or more of their monthly income to be able to afford any one of the housing types.” — Langford Housing Needs Report

Other communities tell a different story. Langford, for instance, has undergone more rapid physical transformation than nearly any municipality in British Columbia. Six-storey buildings, townhomes, and multiplexes now rise alongside modest 1950s bungalows. Of course, rapid growth has consequences: Langford initially sprawled outward, encroaching on natural landscapes, often entrenching car-dependency. But recognizing past mistakes, it has since shifted toward thoughtful infill while remaining committed to abundant housing for families. In essence, Langford accepted physical change to avoid the hollowing out of its community.

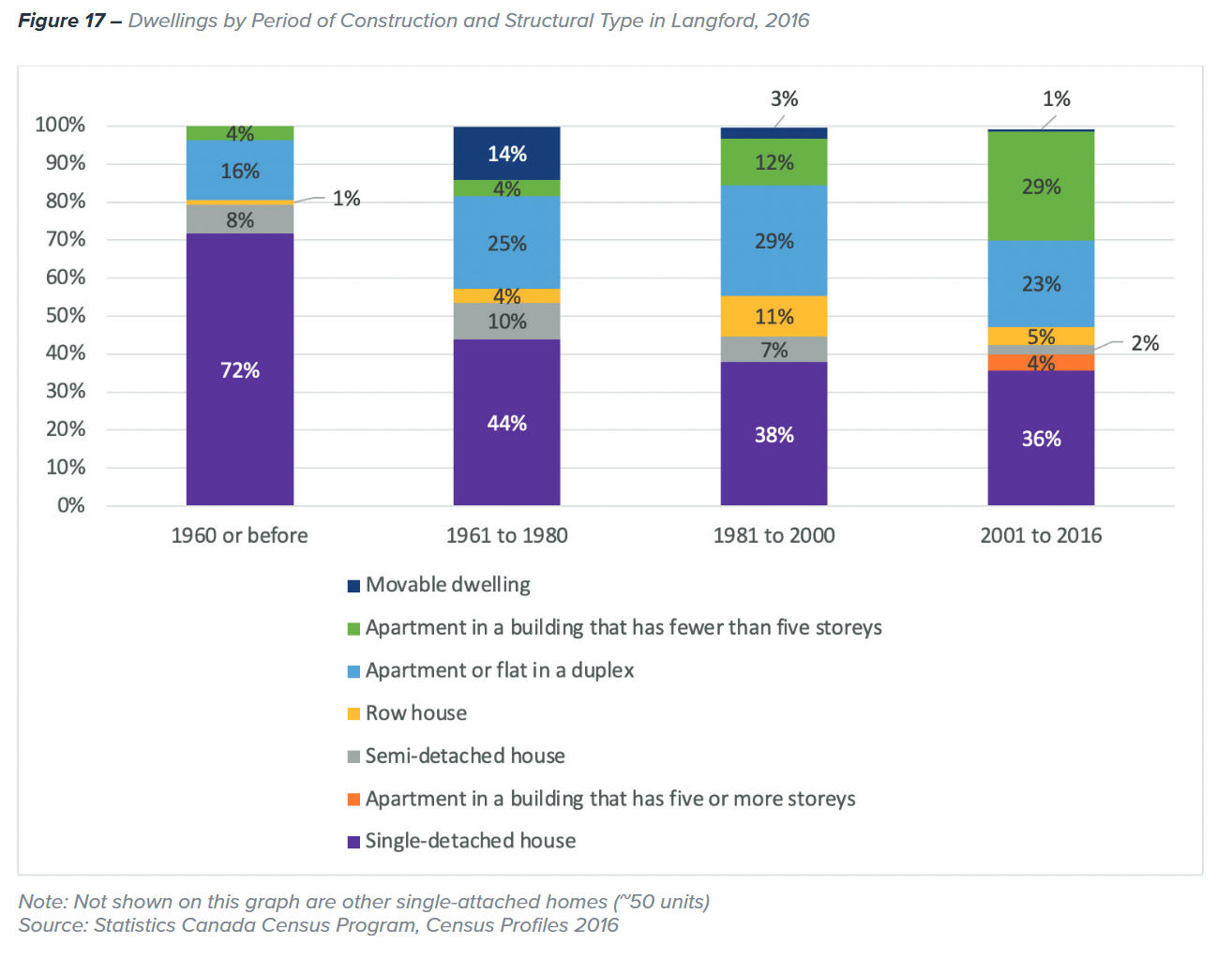

Single-detached houses have consistently dominated housing construction, though there has been proportional growth over time in apartments (both low- and high-rise), row houses, and semi-detached homes. (Langford Housing Needs Report)

Single-detached houses have consistently dominated housing construction, though there has been proportional growth over time in apartments (both low- and high-rise), row houses, and semi-detached homes. (Langford Housing Needs Report)

Compared to Oak Bay, Langford might as well be on a different planet. But they’re just 15 kilometres apart. What Oak Bay sacrificed, Langford preserved—young families flock to Langford, seeking affordability and opportunity, leaving behind communities they can no longer afford to call home. If the problem were simply that no one wished to live in Oak Bay, why are so many choosing Langford when the communities are so similar?

“In December, Kahlon revealed that while West Vancouver had been expected to build 220 homes between September 2023 and September 2024 as part of the province’s five year housing targets for select municipalities, it had built 56. Oak Bay was to build 58 units but only completed 16.” — B.C. appoints housing adviser for Oak Bay […] after targets missed (Times Colonist, 2025)

It wasn’t always this way. Our communities once embraced the importance of building for the future. Between 1951 and 1961, Oak Bay’s population grew by 29%, and West Vancouver’s surged by 45%. But in recent decades, we’ve collectively decided—implicitly or explicitly—that we’ve built enough. Growth that was once natural in our cities has been stymied by the very residents who would love for their children and grandchildren to stay. Today’s generation is expected to manage with a fraction of the housing abundance that previous generations enjoyed. This risks leaving our children with fewer opportunities, forcing them to move elsewhere in search of affordability and growth. If we genuinely value future prosperity, we must reclaim the commitment of our predecessors and ensure the next generation inherits the same opportunities we were afforded. Not through sprawl that forces debt onto future residents, but by using the land and resources we already have to protect our natural reserves while providing needed homes.

This story isn’t new. Young people across the province have been telling it for years. Now Nanaimo faces this same crossroads. The question isn’t whether change will happen—but how we choose to change.

Will we cling to aesthetics rooted in the past at the expense of our children’s futures? Or can we rise to the occasion and build a community reflective of our values—one that supports the aspirations of future generations? If “the purpose of a system is what it does,” then let us ensure our actions build a vibrant, thriving Nanaimo—worthy not just of our memories, but of our children’s futures. Our decisions today will become our legacy.

Let’s choose wisely.